Is Tap Water Safe to Drink? (U.S. Guide for 2025)

Updated on | Water Safety & Home Health (U.S.)

What Does “Safe” Tap Water Actually Mean?

When people ask, “Is tap water safe to drink?” they are really asking if it is unlikely to harm your health over a lifetime of normal use. In the U.S., this idea of “safe” is defined mainly by the Safe Drinking Water Act (SDWA) and EPA drinking water standards.

For public water systems, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has set legally enforceable limits on more than 90 contaminants (called National Primary Drinking Water Regulations). These standards cover things like harmful microbes, disinfectants, disinfection by-products, heavy metals like lead, and many chemicals.

- “Safe” tap water = contaminants are below EPA limits at the tap in most samples.

- Suppliers must monitor water quality and fix problems if standards are violated.

- Utilities must send you an annual Consumer Confidence Report (CCR) with test results.

However, there are caveats:

- Regulations do not cover every possible chemical or contaminant.

- Water can be clean leaving the treatment plant but pick up contaminants from old pipes inside buildings.

- Private wells are not regulated by EPA; well owners are responsible for testing.

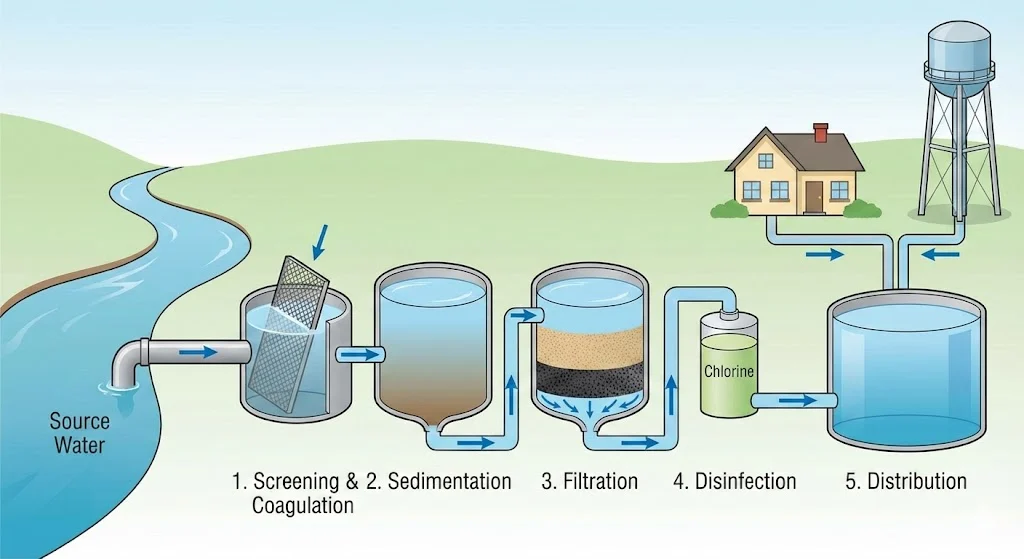

How U.S. Tap Water Is Treated & Regulated

In the United States, about 9 in 10 people get their tap water from a public water system that must meet EPA standards and is monitored by federal, state, and local authorities. These utilities treat water to remove germs and chemicals before it reaches your home.

Typical Journey: From Source to Your Tap

- Source water — rivers, lakes, reservoirs, or underground aquifers.

- Screening & coagulation — removes large particles and suspended solids.

- Filtration — sand, carbon, or membrane filters remove smaller particles, some chemicals, and microbes.

- Disinfection — typically chlorine, chloramine, or UV to kill remaining germs.

- Distribution — water travels through mains and smaller pipes to homes, offices, and schools.

Under the Safe Drinking Water Act, EPA sets Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) or treatment requirements that public systems must follow. Utilities must regularly test their water, report results to state regulators, and notify customers if there is a health-related violation or an acute problem like a microbial outbreak.

Is Tap Water Safe to Drink in the U.S. Overall?

Big picture: for most Americans served by a regulated public water system, tap water is considered safe to drink and is often described as “among the safest drinking water supplies in the world.” At the same time, news reports about lead, PFAS, and other contaminants show that not everyone enjoys the same level of safety.

Here is the reality in simple terms:

- If you live in a town or city with a well-run public utility that meets EPA standards, your tap water is usually safe to drink straight from the tap.

- If your home has old plumbing with lead pipes or fixtures, your risk can be higher even if the utility’s water is clean.

- If you use a private well, safety depends entirely on testing and maintenance because EPA rules don’t apply to private wells.

- If you live in areas with known contamination (for example, industrial sites, military bases, or places with heavy agriculture), your risk may be higher and a filter or alternative source is often recommended.

So the honest answer to “Is tap water safe to drink in the U.S.?” is: usually yes, but it depends on your exact location, plumbing, and personal risk factors.

Main Tap Water Risks in the U.S. (What You Should Know)

1. Lead from Old Pipes & Fixtures

Lead is one of the biggest concerns in older U.S. homes and cities. The danger often doesn’t come from the water treatment plant but from lead service lines, solder, and old brass fixtures in your home or neighborhood.

The EPA’s health goal for lead in drinking water is 0 parts per billion because there is no safe level of lead exposure, especially for children and pregnant women. Utilities must take action if more than 10% of samples exceed 15 parts per billion (the “action level”).

- Who is most at risk? Babies using formula mixed with tap water, small children, pregnant women, and homes built before the 1980s.

- Warning signs: brownish water, metallic taste, or known lead service lines in your area. However, lead often has no taste or color.

- What helps? Testing for lead, using a filter certified to remove lead, replacing lead service lines and old plumbing.

2. PFAS (“Forever Chemicals”)

PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances) are a large family of man-made chemicals used in nonstick cookware, stain-resistant fabrics, firefighting foam, and more. They are called “forever chemicals” because they break down extremely slowly in the environment and can build up in the human body over time.

Recent research and federal assessments suggest that at least about 45% of U.S. tap water may contain one or more PFAS compounds at detectable levels. Exposure has been linked in studies to potential risks including some cancers, immune system effects, high cholesterol, and problems in pregnancy and child development.

Because PFAS contamination can vary drastically from one town to the next, checking your local water report or PFAS-specific data is important if you live near airports, military bases, or industrial sites. Many people in affected areas choose reverse osmosis or specialized PFAS filters for drinking water.

3. Microbial Contamination (Bacteria, Viruses, Parasites)

Germs like E. coli, Giardia, and Cryptosporidium can cause stomach illness, diarrhea, and more serious disease, especially in infants, older adults, and people with weakened immune systems. U.S. utilities disinfect water specifically to control these organisms, but:

- Heavy storms, flooding, or treatment failures can lead to short-term contamination.

- You might receive a Boil Water Advisory if tests show microbial problems.

- Private wells are more vulnerable if they are shallow, poorly constructed, or near septic systems.

In those situations, boiling water for at least one minute (three minutes at higher elevations) kills most harmful germs and is recommended until the advisory is lifted.

4. Disinfection By-Products (DBPs)

Chlorine and other disinfectants are essential to kill germs, but when they react with organic matter in water (like leaves, soil, or algae), they can form disinfection by-products such as trihalomethanes (THMs) and haloacetic acids (HAAs). Long-term exposure at high levels has been linked to possible cancer and reproductive issues, so EPA sets strict limits.

For most U.S. systems, DBP levels stay below regulatory limits. If your utility struggles with DBPs, it will typically show up in your annual water quality report, along with what they are doing about it.

5. Nitrates & Agricultural Contamination

In rural and farming regions, fertilizer and animal waste can increase nitrate levels in groundwater and some surface water sources. High nitrate levels are particularly dangerous for infants under six months, potentially causing a condition known as “blue baby syndrome” that affects oxygen transport in the blood.

Public systems monitor nitrate and must notify customers if levels exceed standards. Private wells near farms, septic systems, or animal operations should be tested regularly (at least annually) for nitrate and bacteria.

Who Should Be Extra Careful with Tap Water?

Even if your local tap water meets regulations, some groups may benefit from extra protection such as a certified filter, boiling water during advisories, or using an alternative source:

- Pregnant people and infants, especially in areas with lead or nitrate concerns.

- Families in older homes with possible lead service lines or plumbing.

- People with weakened immune systems (cancer patients, transplant recipients, etc.).

- People living near industrial sites, military bases, airports, or landfills where PFAS or other chemicals have been reported.

- Private well owners who have not tested their water recently.

Tap vs Bottled vs Filtered Water (U.S. Comparison)

Many U.S. households switch between tap, bottled, and filtered water. Here’s a side-by-side look at how they compare for safety, cost, and convenience.

| Type | How It’s Regulated | Typical Cost (per gallon) | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tap water (public system) | EPA Safe Drinking Water Act standards; regular testing; annual CCR report. | Very low (fractions of a cent; usually $0.01–$0.02 per gallon). | Very affordable, convenient, environmentally friendly; usually safe and reliable. | Quality can vary by city; potential issues with lead pipes, PFAS, or local contamination. |

| Bottled water | Regulated as a food by FDA; not always safer than tap; sometimes just tap water in a bottle. | Expensive: often $0.50–$2.00+ per gallon (sometimes much higher). | Convenient on the go; useful during emergencies or when tap water is temporarily unsafe. | Plastic waste, higher cost, microplastic concerns, not necessarily better quality than good tap water. |

| Filtered tap water | Starts with EPA-regulated tap water; quality depends on filter certification and maintenance. | Filter systems and cartridges add cost but still often cheaper than bottled over time. | Can reduce lead, PFAS, chlorine, off-tastes, and other contaminants; keeps base tap water advantages. | Requires upfront investment and regular cartridge changes; choosing the right filter can be confusing. |

How to Check If Your Tap Water Is Safe (U.S. Step-by-Step)

You don’t need to guess whether your tap water is safe. In the U.S., there are simple tools to verify water quality for your exact address or ZIP code.

✓

U.S. Tap Water Quality Checker

Quickly check official water quality info for your area, then decide if you need a filter.

Tip: Use your ZIP code to find your Consumer Confidence Report (CCR). Look for lead, PFAS, nitrates, and any recent violations. If your report looks worrying, consider testing your tap directly and installing a certified filter.

Step 1: Find Your Consumer Confidence Report (CCR)

If you are on a public water system, your utility must give you a Consumer Confidence Report every year, usually by July 1. The CCR tells you:

- Where your water comes from (river, reservoir, aquifer, etc.).

- Which contaminants were detected and at what levels.

- Whether your system met or violated EPA standards.

- Special notes for vulnerable groups (like infants or immunocompromised people).

You can usually find your CCR on your local utility’s website or via the EPA CCR search tool linked in the checker box above.

Step 2: Check for Lead, PFAS, and Nitrate

When you read your CCR, pay special attention to:

- Lead: Look for action level exceedances. Remember that the health goal is zero.

- PFAS: See if your utility has tested for PFAS and how levels compare to state or federal guidelines.

- Nitrate: Important if you have babies or live near farms.

- Recent violations: Any violations of EPA rules or boil-water notices in the last year.

Step 3: Test Your Home Tap if Needed

Even if the utility’s water is clean, your household plumbing can add contaminants like lead or copper. Consider testing your water if:

- Your home was built before 1986 or has original plumbing.

- You notice unusual color, odor, or taste that persists.

- Someone in your household is pregnant, an infant, or has a compromised immune system.

- You use a private well (should be tested at least annually for bacteria and nitrates, and periodically for other contaminants).

You can buy certified home test kits or work with a state-certified laboratory. Many state health departments provide guidance or low-cost testing options for residents.

Step 4: Choose the Right Filter (If You Need One)

If your CCR or test results show issues, you don’t always need to stop drinking tap water entirely. Often, using a properly certified filter is enough to reduce risk significantly.

- Look for NSF/ANSI certifications that match your concern (e.g., NSF/ANSI 53 for lead, 58 for reverse osmosis, 42 for taste/odor).

- Match the filter to the problem: some filters reduce chlorine and bad taste but do not remove lead or PFAS.

- Maintain your filter: cartridges must be changed on schedule or they can make water quality worse.

Best Practices to Drink Tap Water Safely in the U.S.

If you want the convenience and low cost of tap water but still care about safety, these habits provide a practical middle ground:

- Always read your annual CCR: Set a calendar reminder each year to check for new violations or changes.

- Flush stagnant water: If water has been sitting in pipes for many hours (overnight or after vacation), run the tap for 30–60 seconds before drinking, especially in older homes.

- Use cold water for drinking and cooking: Hot tap water can leach more metals from pipes; heat cold water on the stove or in a kettle instead.

- Consider a point-of-use filter for drinking and cooking water if your area has known issues or you simply want an extra layer of protection.

- Stay alert to local advisories: Sign up for alerts from your utility or city, follow local news, and pay attention to boil-water notices or emergency alerts.

FAQs: Is Tap Water Safe to Drink in the U.S.?

Is U.S. tap water safe to drink?

For most people on a public water system, yes. U.S. tap water is heavily regulated and usually safe to drink. However, local issues like lead pipes, PFAS contamination, or aging infrastructure can increase risk, so it’s important to check your local water quality report.

Is tap water safer than bottled water?

Not always, but in many U.S. cities, good tap water is as safe as or safer than bottled water. Tap water is regulated by EPA, while bottled water is regulated by FDA as a food product. Bottled water is useful in emergencies, but it is more expensive and creates plastic waste.

Can I drink tap water everywhere in the U.S.?

No. Some communities struggle with aging infrastructure, industrial pollution, PFAS, or other local problems. Always check your local CCR, and pay attention to state or local advisories. When traveling, look up the water safety for that specific city or ask locals.

Is tap water safe for babies and pregnant women?

It can be, but extra caution is needed. Lead, nitrate, and certain contaminants are more dangerous for babies and unborn children. Check your CCR, consider testing for lead and nitrate, and ask your healthcare provider whether a filter or bottled water is recommended for formula preparation in your area.

Does boiling tap water make it safe?

Boiling tap water kills many harmful germs, which is why it is recommended during Boil Water Advisories. However, boiling does not remove chemicals like lead, PFAS, or nitrates and can actually concentrate some contaminants as water evaporates. Boiling is mainly for microbial problems, not chemical ones.

What’s the best way to make my tap water safer?

Start by understanding your water. Read your CCR, test if needed, and then choose a filter that is certified for the specific contaminants found in your water. In many cases, filtered tap water offers an excellent balance of safety, taste, and low cost.

Do I need to filter my tap water if the CCR says it’s safe?

Not necessarily. If your water meets standards and you are not in a high-risk group, you may be comfortable drinking straight from the tap. Many people still use filters to improve taste or add an extra safety margin for contaminants like lead or PFAS.

References & Helpful U.S. Resources

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) — Safe Drinking Water Act & Standards

- EPA — Consumer Confidence Reports (Find Your Local Water Quality Report)

- CDC — Drinking Water & Water Quality Information

- U.S. Geological Survey — PFAS in U.S. Tap Water

- EPA — Basic Information About Lead in Drinking Water